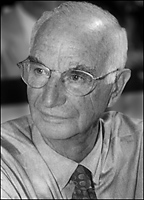

Joe

Henrich and his colleagues are shaking the foundations of psychology

and economics—and hoping to change the way social scientists think about

human behavior and culture.

In the Summer of 1995, a young graduate student in anthropology at UCLA named Joe Henrich

traveled to Peru to carry out some fieldwork among the Machiguenga, an

indigenous people who live north of Machu Picchu in the Amazon basin.

The Machiguenga had traditionally been horticulturalists who lived in

single-family, thatch-roofed houses in small hamlets composed of

clusters of extended families. For sustenance, they relied on local game

and produce from small-scale farming. They shared with their kin but

rarely traded with outside groups.

While the

setting was fairly typical for an anthropologist, Henrich’s research was

not. Rather than practice traditional ethnography, he decided to run a

behavioral experiment that had been developed by economists. Henrich

used a “game”—along the lines of the famous prisoner’s dilemma—to

see whether isolated cultures shared with the West the same basic

instinct for fairness. In doing so, Henrich expected to confirm one of

the foundational assumptions underlying such experiments, and indeed

underpinning the entire fields of economics and psychology: that humans

all share the same cognitive machinery—the same evolved rational and

psychological hardwiring.

The test that Henrich

introduced to the Machiguenga was called the ultimatum game. The rules

are simple: in each game there are two players who remain anonymous to

each other. The first player is given an amount of money, say $100, and

told that he has to offer some of the cash, in an amount of his

choosing, to the other subject. The second player can accept or refuse

the split. But there’s a hitch: players know that if the recipient

refuses the offer, both leave empty-handed. North Americans, who are the

most common subjects for such experiments, usually offer a 50-50 split

when on the giving end. When on the receiving end, they show an

eagerness to punish the other player for uneven splits at their own

expense. In short, Americans show the tendency to be equitable with

strangers—and to punish those who are not.

Among

the Machiguenga, word quickly spread of the young, square-jawed visitor

from America giving away money. The stakes Henrich used in the game

with the Machiguenga were not insubstantial—roughly equivalent to the

few days’ wages they sometimes earned from episodic work with logging or

oil companies. So Henrich had no problem finding volunteers. What he

had great difficulty with, however, was explaining the rules, as the

game struck the Machiguenga as deeply odd.

When

he began to run the game it became immediately clear that Machiguengan

behavior was dramatically different from that of the average North

American. To begin with, the offers from the first player were much

lower. In addition, when on the receiving end of the game, the

Machiguenga rarely refused even the lowest possible amount. "It just

seemed ridiculous to the Machiguenga that you would reject an offer of

free money," says Henrich. "They just didn’t understand why anyone would

sacrifice money to punish someone who had the good luck of getting to

play the other role in the game."

The potential implications of the unexpected

results were quickly apparent to Henrich. He knew that a vast amount of

scholarly literature in the social sciences—particularly in economics

and psychology—relied on the ultimatum game and similar experiments. At

the heart of most of that research was the implicit assumption that the

results revealed evolved psychological traits common to all humans,

never mind that the test subjects were nearly always from the

industrialized West. Henrich realized that if the Machiguenga results

stood up, and if similar differences could be measured across other

populations, this assumption of universality would have to be

challenged.

Henrich

had thought he would be adding a small branch to an established tree of

knowledge. It turned out he was sawing at the very trunk. He began to

wonder: What other certainties about "human nature" in social science

research would need to be reconsidered when tested across diverse

populations?

Henrich soon landed a grant from

the MacArthur Foundation to take his fairness games on the road. With

the help of a dozen other colleagues he led a study of 14 other

small-scale societies, in locales from Tanzania to Indonesia.

Differences abounded in the behavior of both players in the ultimatum

game. In no society did he find people who were purely selfish (that is,

who always offered the lowest amount, and never refused a split), but

average offers from place to place varied widely and, in some

societies—ones where gift-giving is heavily used to curry favor or gain

allegiance—the first player would often make overly generous offers in

excess of 60 percent, and the second player would often reject them,

behaviors almost never observed among Americans.

The research established Henrich as an up-and-coming scholar. In 2004,

he was given the U.S. Presidential Early Career Award for young

scientists at the White House. But his work also made him a

controversial figure. When he presented his research to the anthropology

department at the University of British Columbia during a job interview

a year later, he recalls a hostile reception. Anthropology is the

social science most interested in cultural differences, but the young

scholar’s methods of using games and statistics to test and compare

cultures with the West seemed heavy-handed and invasive to some.

"Professors from the anthropology department suggested it was a bad

thing that I was doing," Henrich remembers. "The word 'unethical' came

up."

So instead of toeing the line, he switched

teams. A few well-placed people at the University of British Columbia

saw great promise in Henrich’s work and created a position for him,

split between the economics department and the psychology department. It

was in the psychology department that he found two kindred spirits in Steven Heine and Ara Norenzayan.

Together the three set about writing a paper that they hoped would

fundamentally challenge the way social scientists thought about human

behavior, cognition, and culture.

A modern liberal arts education gives lots of

lip service to the idea of cultural diversity. It’s generally agreed

that all of us see the world in ways that are sometimes socially and

culturally constructed, that pluralism is good, and that ethnocentrism

is bad. But beyond that the ideas get muddy. That we should welcome and

celebrate people of all backgrounds seems obvious, but the implied

corollary—that people from different ethno-cultural origins have

particular attributes that add spice to the body politic—becomes more

problematic. To avoid stereotyping, it is rarely stated bluntly just

exactly what those culturally derived qualities might be. Challenge

liberal arts graduates on their appreciation of cultural diversity and

you’ll often find them retreating to the anodyne notion that under the

skin everyone is really alike.

If you take a

broad look at the social science curriculum of the last few decades, it

becomes a little more clear why modern graduates are so unmoored. The

last generation or two of undergraduates have largely been taught by a

cohort of social scientists busily doing penance for the racism and

Eurocentrism of their predecessors, albeit in different ways. Many

anthropologists took to the navel gazing of postmodernism and swore off

attempts at rationality and science, which were disparaged as weapons of

cultural imperialism.

Economists and

psychologists, for their part, did an end run around the issue with the

convenient assumption that their job was to study the human mind

stripped of culture. The human brain is genetically comparable around

the globe, it was agreed, so human hardwiring for much behavior,

perception, and cognition should be similarly universal. No need, in

that case, to look beyond the convenient population of undergraduates

for test subjects. A 2008 survey of the top six psychology journals

dramatically shows how common that assumption was: more than 96 percent

of the subjects tested in psychological studies from 2003 to 2007 were

Westerners—with nearly 70 percent from the United States alone. Put

another way: 96 percent of human subjects in these studies came from

countries that represent only 12 percent of the world’s population.

Henrich’s work with the ultimatum game was an example of a small but

growing countertrend in the social sciences, one in which researchers

look straight at the question of how deeply culture shapes human

cognition. His new colleagues in the psychology department, Heine and

Norenzayan, were also part of this trend. Heine focused on the different

ways people in Western and Eastern cultures perceived the world,

reasoned, and understood themselves in relationship to others.

Norenzayan’s research focused on the ways religious belief influenced

bonding and behavior. The three began to compile examples of

cross-cultural research that, like Henrich’s work with the Machiguenga,

challenged long-held assumptions of human psychological universality.

Some of that research went back a generation. It was in the 1960s, for

instance, that researchers discovered that aspects of visual perception

were different from place to place. One of the classics of the

literature, the Müller-Lyer illusion,

showed that where you grew up would determine to what degree you would

fall prey to the illusion that these two lines are different in length:

Researchers found that Americans perceive the

line with the ends feathered outward (B) as being longer than the line

with the arrow tips (A). San foragers of the Kalahari, on the other

hand, were more likely to see the lines as they are: equal in length.

Subjects from more than a dozen cultures were tested, and Americans were

at the far end of the distribution—seeing the illusion more

dramatically than all others.

More recently psychologists had challenged the universality of research done in the 1950s by pioneering social psychologist Solomon Asch.

Asch had discovered that test subjects were often willing to make

incorrect judgments on simple perception tests to conform with group

pressure. When the test was performed across 17 societies, however, it

turned out that group pressure had a range of influence. Americans were

again at the far end of the scale, in this case showing the least

tendency to conform to group belief.

As Heine, Norenzayan, and Henrich furthered their search, they began to

find research suggesting wide cultural differences almost everywhere

they looked: in spatial reasoning, the way we infer the motivations of

others, categorization, moral reasoning, the boundaries between the self

and others, and other arenas. These differences, they believed, were

not genetic. The distinct ways Americans and Machiguengans played the

ultimatum game, for instance, wasn’t because they had differently

evolved brains. Rather, Americans, without fully realizing it, were

manifesting a psychological tendency shared with people in other

industrialized countries that had been refined and handed down through

thousands of generations in ever more complex market economies. When

people are constantly doing business with strangers, it helps when they

have the desire to go out of their way (with a lawsuit, a call to the

Better Business Bureau, or a bad Yelp review) when they feel cheated.

Because Machiguengan culture had a different history, their gut feeling

about what was fair was distinctly their own. In the small-scale

societies with a strong culture of gift-giving, yet another conception

of fairness prevailed. There, generous financial offers were turned down

because people’s minds had been shaped by a cultural norm that taught

them that the acceptance of generous gifts brought burdensome

obligations. Our economies hadn’t been shaped by our sense of fairness;

it was the other way around.

The growing body of

cross-cultural research that the three researchers were compiling

suggested that the mind’s capacity to mold itself to cultural and

environmental settings was far greater than had been assumed. The most

interesting thing about cultures may not be in the observable things

they do—the rituals, eating preferences, codes of behavior, and the

like—but in the way they mold our most fundamental conscious and

unconscious thinking and perception.

For

instance, the different ways people perceive the Müller-Lyer illusion

likely reflects lifetimes spent in different physical environments.

American children, for the most part, grow up in box-shaped rooms of

varying dimensions. Surrounded by carpentered corners, visual perception

adapts to this strange new environment (strange and new in terms of

human history, that is) by learning to perceive converging lines in

three dimensions.

When unconsciously translated

in three dimensions, the line with the outward-feathered ends (C)

appears farther away and the brain therefore judges it to be longer. The

more time one spends in natural environments, where there are no

carpentered corners, the less one sees the illusion.

As the three continued their work, they noticed something else that was

remarkable: again and again one group of people appeared to be

particularly unusual when compared to other populations—with

perceptions, behaviors, and motivations that were almost always sliding

down one end of the human bell curve.

In the end they titled their paper “The Weirdest People in the World?” (pdf)

By “weird” they meant both unusual and Western, Educated,

Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic. It is not just our Western habits

and cultural preferences that are different from the rest of the world,

it appears. The very way we think about ourselves and others—and even

the way we perceive reality—makes us distinct from other humans on the

planet, not to mention from the vast majority of our ancestors. Among

Westerners, the data showed that Americans were often the most unusual,

leading the researchers to conclude that “American participants are

exceptional even within the unusual population of Westerners—outliers

among outliers.”

Given the data, they concluded

that social scientists could not possibly have picked a worse population

from which to draw broad generalizations. Researchers had been doing

the equivalent of studying penguins while believing that they were

learning insights applicable to all birds.

Not long ago I met Henrich, Heine, and

Norenzayan for dinner at a small French restaurant in Vancouver, British

Columbia, to hear about the reception of their weird paper, which was

published in the prestigious journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences

in 2010. The trio of researchers are young—as professors

go—good-humored family men. They recalled that they were nervous as the

publication time approached. The paper basically suggested that much of

what social scientists thought they knew about fundamental aspects of

human cognition was likely only true of one small slice of humanity.

They were making such a broadside challenge to whole libraries of

research that they steeled themselves to the possibility of becoming

outcasts in their own fields.

“We were scared,” admitted Henrich. “We were warned that a lot of people were going to be upset.”

“We were told we were going to get spit on,” interjected Norenzayan.

“Yes,” Henrich said. “That we’d go to conferences and no one was going to sit next to us at lunchtime.”

Interestingly, they seemed much less concerned that they had used the

pejorative acronym WEIRD to describe a significant slice of humanity,

although they did admit that they could only have done so to describe

their own group. “Really,” said Henrich, “the only people we could have

called weird are represented right here at this table.”

Still, I had to wonder whether describing the Western mind, and the

American mind in particular, as weird suggested that our cognition is

not just different but somehow malformed or twisted. In their paper the

trio pointed out cross-cultural studies that suggest that the “weird”

Western mind is the most self-aggrandizing and egotistical on the

planet: we are more likely to promote ourselves as individuals versus

advancing as a group. WEIRD minds are also more analytic, possessing the

tendency to telescope in on an object of interest rather than

understanding that object in the context of what is around it.

The WEIRD mind also appears to be unique in terms of how it comes to

understand and interact with the natural world. Studies show that

Western urban children grow up so closed off in man-made environments

that their brains never form a deep or complex connection to the natural

world. While studying children from the U.S., researchers have

suggested a developmental timeline for what is called “folkbiological

reasoning.” These studies posit that it is not until children are around

7 years old that they stop projecting human qualities onto animals and

begin to understand that humans are one animal among many. Compared to

Yucatec Maya communities in Mexico, however, Western urban children

appear to be developmentally delayed in this regard. Children who grow

up constantly interacting with the natural world are much less likely to

anthropomorphize other living things into late childhood.

Given that people living in WEIRD societies don’t routinely encounter

or interact with animals other than humans or pets, it’s not surprising

that they end up with a rather cartoonish understanding of the natural

world. “Indeed,” the report concluded, “studying the cognitive

development of folkbiology in urban children would seem the equivalent

of studying ‘normal’ physical growth in malnourished children.”

During our dinner, I admitted to Heine, Henrich, and Norenzayan that

the idea that I can only perceive reality through a distorted cultural

lens was unnerving. For me the notion raised all sorts of metaphysical

questions: Is my thinking so strange that I have little hope of

understanding people from other cultures? Can I mold my own psyche or

the psyches of my children to be less WEIRD and more able to think like

the rest of the world? If I did, would I be happier?

Henrich reacted with mild concern that I was taking this research so

personally. He had not intended, he told me, for his work to be read as

postmodern self-help advice. “I think we’re really interested in these

questions for the questions’ sake,” he said.

The

three insisted that their goal was not to say that one culturally

shaped psychology was better or worse than another—only that we’ll never

truly understand human behavior and cognition until we expand the

sample pool beyond its current small slice of humanity. Despite these

assurances, however, I found it hard not to read a message between the

lines of their research. When they write, for example, that weird

children develop their understanding of the natural world in a

“culturally and experientially impoverished environment” and that they

are in this way the equivalent of “malnourished children,” it’s

difficult to see this as a good thing.

The turn that Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan

are asking social scientists to make is not an easy one: accounting for

the influence of culture on cognition will be a herculean task. Cultures

are not monolithic; they can be endlessly parsed. Ethnic backgrounds,

religious beliefs, economic status, parenting styles, rural upbringing

versus urban or suburban—there are hundreds of cultural differences that

individually and in endless combinations influence our conceptions of

fairness, how we categorize things, our method of judging and decision

making, and our deeply held beliefs about the nature of the self, among

other aspects of our psychological makeup.

We

are just at the beginning of learning how these fine-grained cultural

differences affect our thinking. Recent research has shown that people

in “tight” cultures, those with strong norms and low tolerance for

deviant behavior (think India, Malaysia, and Pakistan), develop higher

impulse control and more self-monitoring abilities than those from other

places. Men raised in the honor culture of the American South have been

shown to experience much larger surges of testosterone after insults

than do Northerners. Research published late last year suggested

psychological differences at the city level too. Compared to San

Franciscans, Bostonians’ internal sense of self-worth is more dependent

on community status and financial and educational achievement. “A

cultural difference doesn’t have to be big to be important,” Norenzayan

said. “We’re not just talking about comparing New York yuppies to the

Dani tribesmen of Papua New Guinea.”

As

Norenzayan sees it, the last few generations of psychologists have

suffered from “physics envy,” and they need to get over it. The job,

experimental psychologists often assumed, was to push past the content

of people’s thoughts and see the underlying universal hardware at work.

“This is a deeply flawed way of studying human nature,” Norenzayan told

me, “because the content of our thoughts and their process are

intertwined.” In other words, if human cognition is shaped by cultural

ideas and behavior, it can’t be studied without taking into account what

those ideas and behaviors are and how they are different from place to

place.

This new approach suggests the

possibility of reverse-engineering psychological research: look at

cultural content first; cognition and behavior second. Norenzayan’s recent work on religious belief

is perhaps the best example of the intellectual landscape that is now

open for study. When Norenzayan became a student of psychology in 1994,

four years after his family had moved from Lebanon to America, he was

excited to study the effect of religion on human psychology. “I remember

opening textbook after textbook and turning to the index and looking

for the word ‘religion,’ ” he told me, “Again and again the very word

wouldn’t be listed. This was shocking. How could psychology be the

science of human behavior and have nothing to say about religion? Where I

grew up you’d have to be in a coma not to notice the importance of

religion on how people perceive themselves and the world around them.”

Norenzayan became interested in how certain religious beliefs, handed

down through generations, may have shaped human psychology to make

possible the creation of large-scale societies. He has suggested that

there may be a connection between the growth of religions that believe

in “morally concerned deities”—that is, a god or gods who care if people

are good or bad—and the evolution of large cities and nations. To be

cooperative in large groups of relative strangers, in other words, might

have required the shared belief that an all-powerful being was forever

watching over your shoulder.

If religion was

necessary in the development of large-scale societies, can large-scale

societies survive without religion? Norenzayan points to parts of

Scandinavia with atheist majorities that seem to be doing just fine.

They may have climbed the ladder of religion and effectively kicked it

away. Or perhaps, after a thousand years of religious belief, the idea

of an unseen entity always watching your behavior remains in our

culturally shaped thinking even after the belief in God dissipates or

disappears.

Why, I asked Norenzayan, if religion

might have been so central to human psychology, have researchers not

delved into the topic? “Experimental psychologists are the weirdest of

the weird,” said Norenzayan. “They are almost the least religious

academics, next to biologists. And because academics mostly talk amongst

themselves, they could look around and say, ‘No one who is important to

me is religious, so this must not be very important.’” Indeed, almost

every major theorist on human behavior in the last 100 years predicted

that it was just a matter of time before religion was a vestige of the

past. But the world persists in being a very religious place.

Henrich, Heine, and Norenzayan's fear of

being ostracized after the publication of the WEIRD paper turned out to

be misplaced. Response to the paper, both published and otherwise, has

been nearly universally positive, with more than a few of their

colleagues suggesting that the work will spark fundamental changes. “I

have no doubt that this paper is going to change the social sciences,”

said Richard Nisbett, an eminent psychologist at the University of Michigan. “It just puts it all in one place and makes such a bold statement.”

More remarkable still, after reading the paper, academics from other

disciplines began to come forward with their own mea culpas. Commenting

on the paper, two brain researchers from Northwestern University argued

(pdf) that the nascent field of neuroimaging had made the same mistake

as psychologists, noting that 90 percent of neuroimaging studies were

performed in Western countries. Researchers in motor development similarly suggested

that their discipline’s body of research ignored how different

child-rearing practices around the world can dramatically influence

states of development. Two psycholinguistics professors suggested that their colleagues had also made the same mistake: blithely assuming human homogeneity while focusing their research primarily on one rather small slice of humanity.

At its heart, the challenge of the WEIRD paper is not simply to the

field of experimental human research (do more cross-cultural studies!);

it is a challenge to our Western conception of human nature. For some

time now, the most widely accepted answer to the question of why humans,

among all animals, have so successfully adapted to environments across

the globe is that we have big brains with the ability to learn,

improvise, and problem-solve.

Henrich has

challenged this “cognitive niche” hypothesis with the “cultural niche”

hypothesis. He notes that the amount of knowledge in any culture is far

greater than the capacity of individuals to learn or figure it all out

on their own. He suggests that individuals tap that cultural storehouse

of knowledge simply by mimicking (often unconsciously) the behavior and

ways of thinking of those around them. We shape a tool in a certain

manner, adhere to a food taboo, or think about fairness in a particular

way, not because we individually have figured out that behavior’s

adaptive value, but because we instinctively trust our culture to show

us the way. When Henrich asked Fijian women why they avoided certain

potentially toxic fish during pregnancy and breastfeeding, he found that

many didn’t know or had fanciful reasons. Regardless of their personal

understanding, by mimicking this culturally adaptive behavior they were

protecting their offspring. The unique trick of human psychology, these

researchers suggest, might be this: our big brains are evolved to let

local culture lead us in life’s dance.

The

applications of this new way of looking at the human mind are still in

the offing. Henrich suggests that his research about fairness might

first be applied to anyone working in international relations or

development. People are not “plug and play,” as he puts it, and you

cannot expect to drop a Western court system or form of government into

another culture and expect it to work as it does back home. Those trying

to use economic incentives to encourage sustainable land use will

similarly need to understand local notions of fairness to have any

chance of influencing behavior in predictable ways.

Because of our peculiarly Western way of thinking of ourselves as

independent of others, this idea of the culturally shaped mind doesn’t

go down very easily. Perhaps the richest and most established vein of

cultural psychology—that which compares Western and Eastern concepts of

the self—goes to the heart of this problem. Heine has spent much of his

career following the lead of a seminal paper published in 1991

by Hazel Rose Markus, of Stanford University, and Shinobu Kitayama, who

is now at the University of Michigan. Markus and Kitayama suggested

that different cultures foster strikingly different views of the self,

particularly along one axis: some cultures regard the self as

independent from others; others see the self as interdependent. The

interdependent self—which is more the norm in East Asian countries,

including Japan and China—connects itself with others in a social group

and favors social harmony over self-expression. The independent

self—which is most prominent in America—focuses on individual attributes

and preferences and thinks of the self as existing apart from the

group.

The classic "rod and frame" task: Is the line in the center vertical?

That we in the West develop brains that are

wired to see ourselves as separate from others may also be connected to

differences in how we reason, Heine argues. Unlike the vast majority of

the world, Westerners (and Americans in particular) tend to reason

analytically as opposed to holistically. That is, the American mind

strives to figure out the world by taking it apart and examining its

pieces. Show a Japanese and an American the same cartoon of an aquarium,

and the American will remember details mostly about the moving fish

while the Japanese observer will likely later be able to describe the

seaweed, the bubbles, and other objects in the background. Shown another

way, in a different test analytic Americans will do better on something

called the “rod and frame” task, where one has to judge whether a line

is vertical even though the frame around it is skewed. Americans see the

line as apart from the frame, just as they see themselves as apart from

the group.

Heine and others suggest that such

differences may be the echoes of cultural activities and trends going

back thousands of years. Whether you think of yourself as interdependent

or independent may depend on whether your distant ancestors farmed rice

(which required a great deal of shared labor and group cooperation) or

herded animals (which rewarded individualism and aggression). Heine

points to Nisbett at Michigan, who has argued (pdf)

that the analytic/holistic dichotomy in reasoning styles can be clearly

seen, respectively, in Greek and Chinese philosophical writing dating

back 2,500 years. These psychological trends and tendencies may echo

down generations, hundreds of years after the activity or situation that

brought them into existence has disappeared or fundamentally changed.

And here is the rub: the culturally shaped analytic/individualistic

mind-sets may partly explain why Western researchers have so

dramatically failed to take into account the interplay between culture

and cognition. In the end, the goal of boiling down human psychology to

hardwiring is not surprising given the type of mind that has been

designing the studies. Taking an object (in this case the human mind)

out of its context is, after all, what distinguishes the analytic

reasoning style prevalent in the West. Similarly, we may have

underestimated the impact of culture because the very ideas of being

subject to the will of larger historical currents and of unconsciously

mimicking the cognition of those around us challenges our Western

conception of the self as independent and self-determined. The

historical missteps of Western researchers, in other words, have been

the predictable consequences of the WEIRD mind doing the thinking.